The second-biggest secret parents keep from their children is this: Training wheels in no way truly prepare you for riding a bike alone. They just don’t.

This is what makes learning to ride a bike so unforgettable. The entire process is unnatural. There is no way to ease into it, because it takes speed and faith to keep a bike balanced. Sure, there are the aforementioned training wheels and metal bars for a parent to hold, but a child cannot balance on his own two wheels until he is actually doing it.

It’s like walking: Either you’re walking, or you’re just standing there. There isn’t much in-between room. This is why we always remember a child’s first steps. The instant he lets go of the couch and trusts that his right leg will follow the left is a miraculous thing. No one can make a child do it. It just happens.

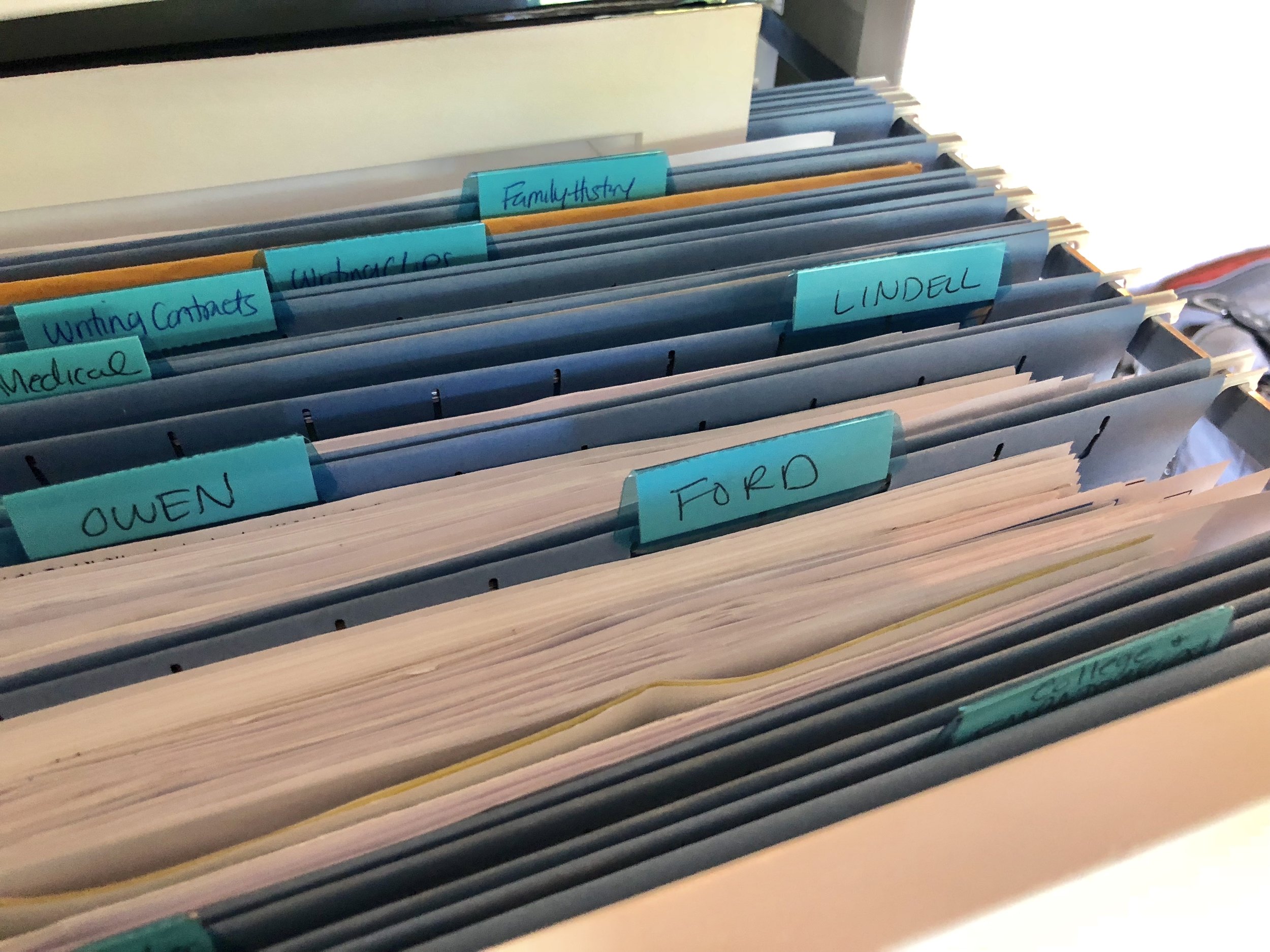

I was truly horrified when Ford learned to ride a bike eight years ago. I actually needed to go inside and let Dustin handle the lessons. In one afternoon, my firstborn child became intimately familiar with the pavement — except for the time he catapulted himself forward off the bike and landed in a bush.

Things were different when Owen learned to ride a bike. While Ford goes at life full throttle, Owen is a bit more cautious. He would like you to jump off the rock into the lake before he tries it. And even then, peer pressure is no match for Owen’s will of steel. He seemed to look at the two-wheeled contraption we bought for him and say, “If God had wanted us to ride bikes, wouldn’t he have built them?”

Again, I asked Dustin to handle the lessons. I couldn’t watch.

Turns out, however, there was nothing to watch. Owen wasn’t having any part of this “balance on two spinning wheels” thing.

He did like the helmet, though.

Then one day, Ford came running into the house. “Come outside and see, Owen,” he said.

I stepped onto the front porch, and, just like that, Owen was riding his bike without training wheels. Ford had taught him.

I hoped the same thing would happen with Lindell. If Owen has a will of steel, Lindell’s is super-glued, secured with plastic ties and locked down with a deadbolt that I assure you has no key. Seriously, we’ve tried all the tricks: bribes, pressure, chocolate. When Lindell doesn’t want do something, not even a cupcake will convince him. When you try to put him on a boat, he is like the dog that literally shimmies its head out of the collar. He can make his legs turn to jelly like nobody’s business, or he can make his body as stiff as a board — really unwelcome when he was younger and we tried to get him in his carseat. If all else fails, there’s always screaming. And Lindell can scream.

In other words, I would eat rotten asparagus before I’d try to teach my youngest how to ride a bike.

But Dustin gave it a shot.

They did the training wheels and the metal bar sticking off the back. Lindell played along for a couple of years, probably just to see his dad running up and down the street. Riding bikes was always a “dad thing” for Lindell. “I’ll try again when dad is home,” he’d say. It was like Lindell could smell my fear.

Ford and Dustin in 2007

Then one day he said, “Mom, it’s time for you to teach me how to ride my bike.” I started to explain that no one can really learn how to ride a bike. You just need to do it. But saying that goes against every sort of parent code. It’s best to let them think the training wheels will somehow make it all easier.

So we went outside, and I reluctantly ran up and down our street holding on to the back of Lindell’s bicycle seat. There is a video of this, and it’s not attractive. No one runs gracefully when they have one hand fixed to a seat. We went back and forth, up and down, until sweat ran down my temples.

And then I let go. But Lindell didn’t know it. He rode to the end of the street by himself. When he stopped and turned around, I yelled, “See? You did it!”

Lindell was angry I had let go.

All I felt was sad. My last child can ride a bike. There is no one to run behind, no bicycle seat to hold. Yes, I had released the bike, but I knew it was Lindell who was letting go. He did it so naturally, and yet it felt so unnatural to me.

Which, of course, is the first biggest secret parents keep from their children: We never really wanted to let go.

This column also appears in Sarah Smiley's book, Got Here as Soon as I Could.